The New Insider Trading Landscape: United States v. Newman and Its Impact on Pending Insider Trading Prosecutions

On December 10, 2014, the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit vacated the convictions of two hedge fund portfolio managers for trading on material non-public or "inside," information that came to the managers third- and fourth-hand, through an attenuated chain of "tippees" originating with corporate insiders that the defendants didn't even know.1

Almost immediately, media coverage hailed the Court's opinion as a game-changer that "upended" the recent high-profile campaign to crack down on insider trading, "rewrote the insider trading playbook" and "imposed the greatest limits on prosecutors in a generation."2 Within 24 hours, the Manhattan U.S. Attorney warned that the ruling would "limit the ability to prosecute people who trade on leaked inside information,"3 the chairwoman of the S.E.C. expressed concern that the opinion imposed an "overly narrow view of the insider trading law"4 and at least one federal judge raised questions about whether an insider-trading case pending before him could proceed in light of the ruling.5

The interest in Newman is understandable. From August 2009 to July 2014, the Manhattan U.S. Attorney charged 85 defendants with insider trading and obtained convictions against all but one.6 If Newman indeed rewrites insider trading law, the decision could, perhaps, threaten the validity of many high-profile convictions and terminate a years-long insider trading crack-down that, until now, showed no signs of slowing. This article briefly explains current federal insider trading law leading up to and including Newman and then assesses Newman's potential impact on some pending cases.

Introduction to Insider Trading Liability

In the United States, no law or regulation expressly prohibits buying or selling stock on the basis of material non-public information. Federal law does prohibit fraud "in connection with the purchase or sale of any security,"7 however, and courts have long considered certain kinds of insider trading to fall within the general ban on securities fraud.8 Thus, insider trading is only illegal when it constitutes fraud.

The common law of fraud prohibits lying to a counterparty to induce them to enter into a transaction, but buyers and sellers are not normally required to affirmatively disclose material information to one another about the transaction. Rather, the failure to disclose information constitutes fraud only if a party had an affirmative duty to disclose that information. Such an obligation "arises when one party has information ‘that the other [party] is entitled to know because of a fiduciary or other similar relation of trust and confidence between them.'"

Courts have long recognized a fiduciary relationship of trust and confidence between a corporation's shareholders and corporate insiders (e.g., directors and officers) possessing inside information, which, under the so-called "classical theory" of insider trading, "gives rise to a duty to disclose or abstain from trading because of the necessity of preventing a corporate insider from taking advantage of uninformed stockholders."9 In addition to the "classical" theory, courts have also imposed liability under a distinct, "misappropriation" theory that extends liability to certain outsiders who obtain inside information about the corporation (e.g., an outside lawyer), and who subsequently breach a fiduciary duty to the source of that information by secretly converting it for personal gain, either by trading upon it directly or passing it on to others.10

Under either theory, recipients of inside information, or "tippees" that profit from confidential information leaked by an insider or misappropriator for personal gain in breach of a fiduciary duty may be held liable as after the fact participants in the initial breach.11 Because insider trading liability is premised on self-dealing in breach of a fiduciary duty, it is well-established that any downstream tippee liability requires that the tipper have received some personal benefit from the disclosure. Where the tipper received no personal benefit, tippees that subsequently trade on confidential information will not be liable.12

Courts also agreed, before Newman, that, to be guilty of insider trading, the tippee must have known at least that the tipper breached a duty of confidentiality, but recent insider trading cases provided conflicting guidance on what the tippee must have known about any personal benefit to the tipper. This uncertainty stemmed in part from a 2012 Second Circuit ruling in S.E.C. v. Obus, which articulated a standard for tippee liability that expressly required the tippee to know that the tipper breached a duty, but did not expressly mention the tippee's knowledge that the tipper received a personal benefit.13

District court opinions after Obus conflict as to whether the tippee must know of a personal benefit to the tipper; with two district judges finding that the requirement persists, and the lower Court ruling in Newman finding, to the contrary, that such knowledge was no longer required in light of Obus.14 The Second Circuit's opinion (summarized below), clearly confirms that insider trading by a tippee requires proof that a tippee knew that the source of inside information received a personal benefit.15

United States v. Newman

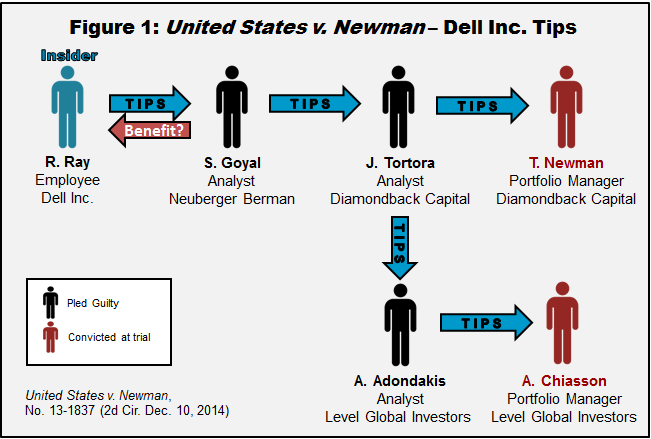

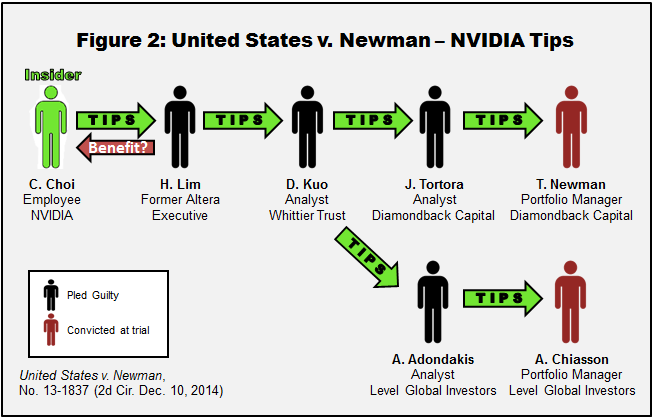

In Newman, two hedge fund portfolio managers were convicted of insider trading and conspiracy for trading Dell and NVIDIA stock on the basis of inside information that the fund managers received through an attenuated chain of downstream tippees several steps removed from the insiders who first leaked the information.

In particular, defendants received confidential Dell, Inc. earnings data that originated with a Dell employee tipping earnings numbers not yet released to a Wall Street analyst who, in turn, passed the information to other tippees, ultimately reaching defendants Newman and Chiasson third- and fourth-hand, respectively. (See Figure 1)

Defendants similarly received confidential NVIDIA Corp. earnings data tipped by a NVIDIA employee and passed through three other tippees before reaching Newman and Chiasson. (See Figure 2)

Defendants did not dispute receiving information from analysts at their respective hedge funds that may have originated with the alleged insiders, but rather focused at trial on establishing that they were unaware of the circumstances surrounding the insiders' disclosure to the first tippees. Both defendants were convicted after a six-week trial.

On appeal, the fund managers argued: (1) that the trial court had erroneously failed to instruct the jury that defendants could only be found guilty if the Government proved beyond a reasonable doubt that defendants knew the corporate insiders had received personal benefits in exchange for the tips; and (2) that the evidence presented at trial was insufficient to prove that the insiders actually had received personal benefits.

The Court agreed on both points and vacated the convictions. First, drawing heavily from S.E.C. v. Dirks, the Court found that the trial judge erred by refusing to instruct the jury on the necessity of defendants' knowledge of a personal benefit to the insiders for tipping the inside information. The Court explained that "the exchange of confidential information for personal benefit is not separate from an insider's fiduciary breach, it is the fiduciary breach that triggers liability." Accordingly, "without establishing that the tippee knows of the personal benefit received by the insider in exchange for the disclosure," the Government fails to show, as it must, "that the tippee knew of breach."

Second, the Court then proceeded to examine the sufficiency of the evidence that the insiders received personal benefits, and that the defendants knew of the benefit. Strikingly, the Court raised the bar for establishing personal benefit, holding that a benefit may be inferred only upon "proof of a meaningfully close personal relationship that generates an exchange that is objective, consequential and represents at least a potential gain of a pecuniary or similarly valuable nature."17

Applying this principal, the Court reviewed the evidence and found that no rational jury could conclude the Government's evidence established that the insiders received any benefit whatsoever for the tips, that defendants knew of any such benefit or even that defendants knew the tips "originated with corporate insiders." The Court explained that circumstantial evidence of casual acquaintances between a tipper and tippee, offers of generic career advice and occasional socializing was insufficient to show the necessary personal benefit to the insider. The Court also concluded it was "largely uncontroverted that [defendants] and even their analysts . . . knew next to nothing about the insiders and nothing about what, if any, personal benefit had been provided to them."

The decision heightens the Government's burden for prosecuting insider trading charges in two respects. First, it holds that the Government must prove that the defendant who allegedly traded on insider information knew that the insider who disclosed the information received a benefit for doing so, even where the defendant had no direct interaction with the insider and received the information indirectly through other tippees. Second, the Court raised the bar for what constitutes a "personal benefit," ruling that the Government must prove that the insider received more than mere friendship in return for disclosing the confidential information.

On January 23, 2015, the Manhattan U.S. Attorney's office announced that it intended to appeal Newman by requesting that the Second Circuit agree to rehear the matter en banc. If that request is granted, the Government will have the opportunity to reargue Newman before a full panel of the circuit court.16 A few days later, on January 26, 2015, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission filed a motion, joining in the prosecutors' request for a hearing en banc. In that filing, the SEC regulators argued for the continued vitality of considering friendship to qualify as a "personal benefit" for insider trading purposes, contending that "[t]he panel's narrowed definition of personal benefit and lack of clarity about the evidence required for establishing such benefit could negatively affect the SEC's ability to bring insider trading actions."

If the request for en banc hearing is rejected, the Government will have the option of seeking to appeal the decision before the United States Supreme Court.

Early Impacts of Newman on Recent and Pending Cases

Predictions that Newman will dramatically alter the face of insider trading law may be premature, since much of the ruling's ultimate significance will inevitably turn on how district courts interpret the reinvigorated standards it sets out. Nonetheless, a review of recent and pending insider trading cases reveals that the new ruling has already been applied in several pending insider trading cases and a review of potential impacts on pending cases nonetheless offers some insight into the post-Newman insider trading landscape.

United States v. Steinberg and Other Related Cases

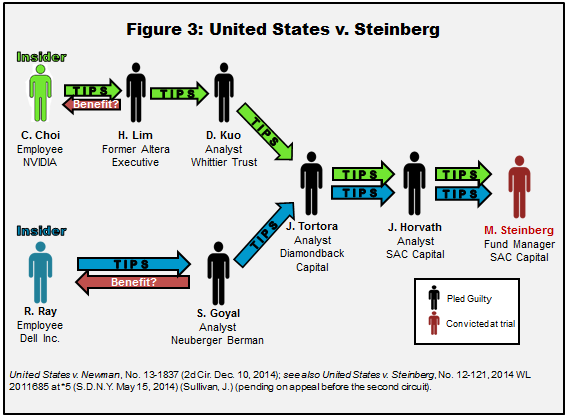

The most obvious impact of Newman will likely be on the related appeal of former SAC Capital Fund Manager Michael Steinberg, currently pending before the Second Circuit. That case arises from essentially the same facts as Newman and presenting virtually identical issues regarding the conviction of a portfolio manager that traded on inside information received through an attenuated chain of tippees.17, 18 (See Figure 3 and compare with Figures 1 and 2)

The Second Circuit lifted a stay of proceedings in Steinberg on December 10th, when it issued the opinion in Newman. Steinberg was tried separately before Judge Sullivan, and, therefore, technically presents a distinct record from that before the Second Circuit in Newman, but the Government doesn't appear to have presented different evidence during the Steinberg proceeding of personal benefits received by the corporate insiders than that presented in Newman, providing little reason to anticipate a different result. Most recently, on January 28, 2015, the S.E.C. stayed a pending administrative appeals proceeding concerning the Commission's prior decision to ban Steinberg from the securities industry.19

Additionally, some Defendants that pled guilty to insider trading and testified in Newman may now seek to withdraw those guilty pleas, since the Second Circuit determined that based on the Government's evidence. "It would not be possible . . . for a jury in a criminal trial to find beyond a reasonable doubt that Ray [the same Dell insider who was the source of a tip at issue in Steinberg] received a personal benefit in exchange for the disclosure of insider information."20 Moreover, the Court explained that the personal benefit element "is not separate," but instead "is the fiduciary breach that triggers liability." Accordingly, the reasoning in Newman likewise precludes assigning liability against any defendants arising from tips originating with Ray, or, arguably, with Choi—unless the Government could present additional evidence sufficient to show a personal benefit to those insiders, which appears unlikely here.

Defendants that pled guilty but who apparently have not yet been sentenced—including Lim, Kuo, Tortora, Adondakis and Horvath—may be able to assert reasonable arguments for withdrawing their pleas under F.R.Cr.P. 11(d)(2)(B), which authorizes withdrawal upon a showing of any "fair and just reason for requesting the withdrawal."21 In determining whether this standard is satisfied, courts in the Second Circuit consider three factors, including "(1) whether the defendant has asserted his or her legal innocence in the motion to withdraw the guilty plea; (2) the amount of time that has elapsed between the plea and the motion (the longer the elapsed time, the less likely the withdrawal would be fair and just); and (3) whether the Government would be prejudiced by a withdrawal of the plea." United States v. Schmidt, 373 F.3d 100 (2d Cir.2004).22

Another interesting question is whether Newman could have any impact on the corporate criminal charges against the fund itself, SAC Capital Advisors, which pled guilty to charges of securities fraud and wire fraud in November 2013.30 On April 10, 2014, U.S. District Judge Laura Taylor Swain, presiding over the criminal action, approved a joint criminal and civil settlement in which the fund agreed to roughly $1.8 billion in penalties to resolve allegations that it allowed rampant insider trading by its employees. As part of the settlement, S.A.C. admitted insider trading by six employees, including Jon Horvath, the analyst alleged to have passed along the Dell and NVIDIA tips at issue in Steinberg. Other insider trading allegations underlying the fund's guilty plea do not involve the kind of attenuated series of tippees presented in Newman. Moreover, the S.A.C. entities charged in that case have, by now, long paid the penalties agreed upon in the settlement agreement.24 As a result, it is very unlikely that the Newman could have any practical impact on the finality of that settlement, the terms of which prohibit the S.A.C. funds, now rebranded as Point72 Asset Management, from managing capital for outside investors.

U.S. v. Conradt

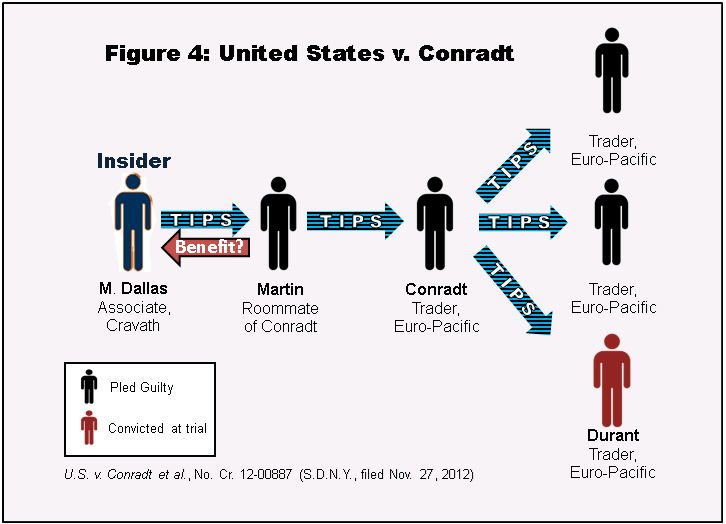

Newman has already had an impact on several insider trading cases arising from unrelated facts. One of the first examples, U.S. v. Conradt et al., involved an insider trading prosecution of five defendants pending before District Judge Andrew Carter in the Southern District of New York. Four of the five defendants have pled guilty to trading on inside information concerning IBM Corp.'s $1.2 billion purchase of SPSS Inc.25

The Conradt defendants included four traders at Euro-Pacific and one of the trader's roommates, an investment banking analyst. The Government alleged that the banking analyst had received the tip from a friend who was an associate at Cravath, Swaine & Moore and who had been working on the IBM deal. After receiving the tip, the banking analyst allegedly passed it along to his roommate, one of the Euro Pacific traders, who then tipped the three other traders, all of whom allegedly traded on the information. (See Figure 4)

The Government's Indictment in Conradt contains no obvious allegations that the Cravath associate who provided the inside information received any "objective, consequential" personal benefit representing the potential gain of a pecuniary gain in exchange for that disclosure.

The day after the Second Circuit's ruling in Newman, Judge Carter scheduled a status conference for December 18th to determine whether the Second Circuit's ruling affected the guilty pleas of the four former traders and the analysts who admitted to an insider trading scheme.26 After hearing from the parties during the hearing, Judge Carter indicated that he had serious doubts about whether there was a sufficient factual basis for the guilty pleas, but agreed to the Government's request for several weeks to prepare briefing on the issue seeking to distinguish Conradt from Newman on the basis that the initial tipper in Conradt was not a corporate insider.27 (The trial of the only defendant that had not yet pled guilty was rescheduled until late February).

On January 12, 2015, the Government filed a brief supporting the sufficiency of the defendants' guilty pleas, arguing that the Second Circuit's holding in Newman was limited to cases brought under the so-called "classical" theory of insider-trading liability — cases in which the tipper is a corporate insider, who owes fiduciary duties to the corporation and its shareholders. Because Conradt was brought under the "misappropriation" theory of insider trading, in which the tipper is a corporate outsider, who misappropriates confidential information in breach of a fiduciary duty owed to the source of the information, the Government contended, Newman should not apply.

On January 25, 2015, U.S. District Judge Andrew L. Carter, Jr. rejected the Government's invitation to limit the Second Circuit's decision in Newman to classical insider-trading cases and vacated the four insider trading guilty pleas at issue. Judge Carter emphasized the Second Circuit's "unequivocal" admonishment that "the elements of tipping liability are the same, regardless of whether the tipper's duty arises under the ‘classical' or ‘misappropriation' theory."

Shortly after that ruling, on January 28, 2015, assistant U.S. Attorney Andrew Bauer wrote to the Court requesting permission to drop the charges against all five defendants, conceding that the recent Second Circuit opinion "substantially changed the law pertaining to insider trading." At a hearing the following day, Bauer told Judge Carter that, in light of "this new, heightened standard under Newman, we do not have the requisite evidence to establish one of the elements of the crime," referring to the re-invigorated personal benefit requirement. If the Second Circuit's decision is reversed, the government would consider charging all five defendants again, assuming the statute of limitations has not run out, Bauer said. The Court promptly granted the Government's request for dismissal without prejudice.

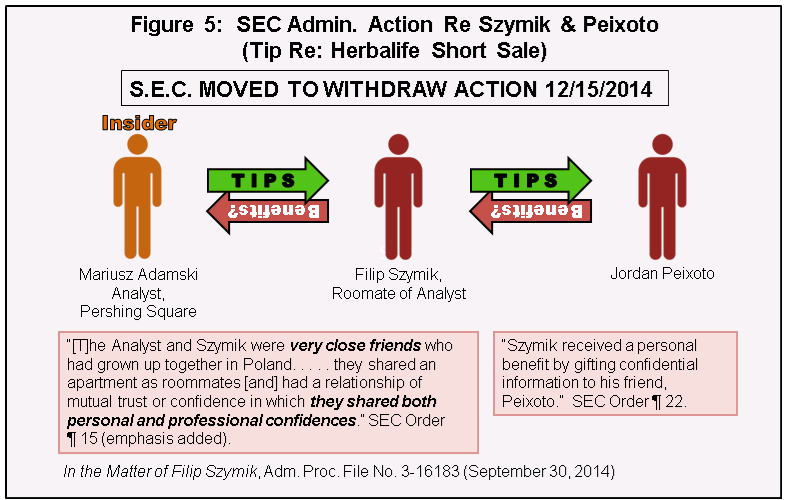

In the Matter of Filip Szymik28

In September 2014, the S.E.C. initiated an administrative action charging two defendants with insider trading on a prominent hedge fund manager Bill Ackerman's announcement that his hedge fund, Pershing Square Management, had formed a negative view of Herbalife Ltd. The S.E.C. alleged that a Pershing analyst tipped Pershing's intention to take a short position on Herbalife Ltd. to his roommate, Filip Szymik, who in turn tipped that information to another friend, Jordan Peixoto. The S.E.C. alleged both Szymik and Peixoto traded illegally on the information. (See Figure 5)

Less than one week after the Second Circuit's ruling in Newman, the S.E.C. moved to withdraw the action. The S.E.C. Enforcement Division officially indicated that its basis for requesting withdrawal was the departure of two key witnesses to Poland, where they reside. The S.E.C. declined to comment on any effect the Second Circuit's ruling may have had on the agency's assessment of the action, but analysts have widely credited the withdrawal at least in part to the heightened showings imposed on prosecutors by Newman.29

As discussed above, Newman clarifies that, to establish a breach of fiduciary duty necessary for insider trading liability, the Government must show that the insider who disclosed the information received in return something more than friendship, with either "objective, consequential" or of "potential pecuniary" value. Notably, the S.E.C.'s allegations filed in September do not appear to allege that the insider analysts received any benefit for disclosing the information, except that "the Analyst and Szymik were very close friends who had grown up together in Poland," that "[f]rom 2008 to April 2013, they shared an apartment as roommates in New York, New York," and that "[t]he Analyst and Szymik had a relationship of mutual trust or confidence in which they shared both personal and professional confidences."30

Conclusion

In the coming months, numerous other criminal defendants and courts will no doubt continue to examine Newman and its early progeny. Two additional examples that may yield relevant rulings in this area include the cases of Michael Kimelman and Matthew Musante. The first involves a former lawyer and trader with the Galleon Group convicted of insider trading in June 2011 who has already served his sentence but may nevertheless seek to capitalize on Newman to attack his conviction.31 The second example, and perhaps the first outside of New York, involves a defendant residing in Florida who previously pled guilty to insider trading charges brought in the Western District of North Carolina in connection with an alleged insider trading ring.32 Musante's lawyer recently filed a motion seeking to withdraw Musante's prior guilty plea, arguing that the attorney's failure to counsel his client on possible defenses presented by the Second Circuit's recent landmark ruling constituted ineffective assistance of counsel.33 Whatever the outcome of these defendants' efforts, in house and outside counsel practicing in this area will need to keep an eye on the continuing developments in insider trading law brought about by the Second Circuit's landmark ruling.

- United States v. Newman, Nos. 13-1837, 13-1917, --- F.3d ----, 2014 WL 6911278 (2d Cir. Dec. 10, 2014).

- See, e.g., Ben Protess, Appeals Court Deals Setback to Crackdown on Insider Trading, N.Y. TIMES, Dec. 10, 2014; Matthew Goldstein, Some Accused of Insider Trading May Rethink Their Guilty Pleas, N.Y. TIMES (Dec. 11, 2014); Peter Henning, Fallout for the S.E.C. and the Justice Dept. From the Insider Trading Ruling, N.Y. TIMES, Dec. 15, 2014.

- U.S. Attorney's Office Southern District of New York, Statement of Manhattan U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara On The U.S. Court Of Appeals Second Circuit Decision In U.S. v. Todd Newman And Anthony Chiasson (Dec. 10, 2014).

- Evelyn Cheng, SEC's White: Insider trading ruling ‘a concern', CNBC (Dec. 11, 2014).

- See U.S. v. Conradt et al., No. Cr. 12-00887 (S.D.N.Y., filed Nov. 27, 2012); Michael Lipkin, Judge Asks For Newman's Effect On Insider Trading Pleas, LAW360 (December 11, 2014).

- See Rachel Abrams, Defense Lawyer Ends Preet Bharara's Streak in Insider Trading Cases, N.Y. TIMES, July 9, 2014; Julia La Roche, Here's Preet Bharara's Amazing 79-0 Insider Trading Conviction Score Card, BUSINESS INSIDER, Feb. 6, 2014 (providing a list of convictions through February 2014).

- Section 10(b)(5) of the Securities Act of 1934, 15 U.S.C. § 78j(b), and a related regulation promulgated by the Securities and Exchange Commission ("S.E.C."), 17 C.F.R. § 240.10b–5.

- See Chiarella v. United States, 445 U.S. 222, 233 (1980).

- Newman, 2014 WL 6911278, at *4 (citations omitted).

- S.E.C. v. Obus, 693 F.3d 276 (2d Cir. 2012) ("[a] second theory, grounded in misappropriation, targets persons who are not corporate insiders but to whom material non-public information has been entrusted in confidence and who breach a fiduciary duty to the source of the information to gain personal profit in the securities market") (citing United States v. O'Hagan, 521 U.S. 642, 652–53 (1997)).

- See Dirks v. S.E.C., 463 U.S. 646, 650 (1983) ("the transactions of those who knowingly participate with the fiduciary in such a breach are as forbidden as transactions on behalf of the trustee himself. . . . Thus, the tippee's duty to disclose or abstain is derivative from that of the insider's duty. . . . The tippee's obligation has been viewed as arising from his role as a participant after the fact in the insider's breach of a fiduciary duty'") (citations omitted).

- In Dirks, for example, a former employee disclosed inside information concerning allegedly fraudulent activity at the company in the hope that Dirks, a tippee, would investigate further and expose the fraud. Id. Because the original tipper did not receive a personal benefit, the Court found no evidence of breach of a fiduciary duty capable of supporting criminal liability for Dirks or the downstream tippees he had informed. Id. at 633 ("Whether disclosure is a breach of duty therefore depends in large part on the purpose of the disclosure. . . . [T]he test is whether the insider personally will benefit, directly or indirectly, from his disclosure.").

- 693 F.3d at 289; see also United States v. Jiau, 734 F.3d 147, 152‐53 (2d Cir. 2013) (articulating substantially the same standard as Obus).

- Compare United States v. Whitman, 904 F. Supp. 2d 363, 370 (S.D.N.Y. 2012) (Rakoff, J.) (in order to be liable, a tippee must know that the tipper received some type of personal benefit) and United States v. Rajaratnam, No. 13‐211 (S.D.N.Y. July 1, 2014) (Buchwald, J.) (dismissed two of the Government's three insider trading counts on the ground that a reasonable jury could not find that Rajaratnam had knowledge that the tipper received a personal benefits) with United States v. Newman, No. 12‐121, 2013 WL 1943342, at *2 (S.D.N.Y. Dec. 6, 2012) (Sullivan, J.) (interpreting Obus as making "clear that the tipper's breach of fiduciary duty and receipt of a personal benefit are separate elements and that the tippee need know only of the former").

- Newman, 2014 WL 6911278, at *1–*3.

- See Christopher Matthews, Review Sought of Appeals-Court Decision in December Limiting Ability to Pursue Cases, THE WALL STREET JOURNAL, Jan. 23, 2015.

- See Patricia Hurtado, SEC Joins U.S. Prosecutors Seeking to Reverse Insider Ruling, BLOOMBERG NEWS, Jan. 26, 2015.

- No. 12‐121, 2014 WL 2011685 at *5 (S.D.N.Y. May 15, 2014) (Sullivan, J.).

- The administrative appeal is S.E.C. Administrative Proceedings No. 3-15925.

- Newman, 2014 WL 6911278, at *11 (emphasis added).

- A defendant that had pled guilty and been sentenced would likely face a more difficult procedural process for vacating their guilty pleas, which would, most likely, require pursuing a collateral attach of the sentence under 28 U.S.C. 2255. Only one defendant in Newman, Anthony Scolaro, appears to fall into this category, but Mr. Scolaro's sentence of three years' probation concludes in 2015.

- The criminal case is United States v. S.A.C. Capital Advisors, L.P., et al., 13 Cr 541 (LTS) in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York (see criminal Indictment, filed July 23, 2013; DOJ press release, Nov. 4, 2013; plea agreement and stipulation of settlement, submitted Nov. 4, 2013). The civil case, also settled via the agreement and stipulation, is United States v. S.A.C. Capital Advisors, L.P., et al., 13 Civ. 5182 (RJS), in the same court.

- The settlement also admitted insider trading by Noah Freeman, Richard Lee, Donald Longeuil, Richard C.B. Lee, and Wesley Wang.

- U.S. v. Conradt et al., No. Cr. 12-00887 (S.D.N.Y., filed Nov. 27, 2012) (see Indictment filed June 2009); see also related SEC civil complaint.

- See Lipkin, note 5, supra.

- Max Stendahl, Newman Ruling Jeopardizes IBM Insider Trading Pleas: Judge, LAW360, December 18, 2014.

- S.E.C. Adm. Proc. File No. 3-16183 (September 30, 2014) (Order Instituting Cease-And Desist Proceedings).

- See James Sterngold, Charges Dropped After Insider-Trading Ruling, WALL STREET JOURNAL, Dec. 15, 2014; Matthew Goldstein, S.E.C. Seeks to Dismiss Insider Trading Lawsuit Involving Herbalife Shares, N.Y. TIMES, Dec. 15, 2014; Matt Levine, Levine on Wall Street: Ruble Trouble and Personal Benefit, BLOOMBERG VIEW, Dec. 16, 2014 ("the Securities and Exchange Commission's insider trading case against the friend of a roommate of an analyst at Pershing Square for trading on information about Pershing Square's plans for Herbalife seems to have collapsed, possibly in part because of the Newman decision . . .").

- See S.E.C. Order, note 35, supra.

- USA v. Musante et al., 12-cr-00386 (W.D. North Carolina, filed Dec. 12, 2012).

- See Musante's Motion to Withdraw Guilty Plea (filed January 27, 2015).